Many Malaysians have probably dealt with the annoyance of a neighbour’s car parked right in front of their house or even inside their property without permission.

While it’s undeniably inconvenient and raises questions about respect for personal boundaries, can these neighbours actually face any consequences?

When talking to them doesn’t bear any fruit, and the neighbours still repeat their actions, there are several legal actions you can take. These include reporting the matter to the relevant authorities, which may take action under these legal provisions:

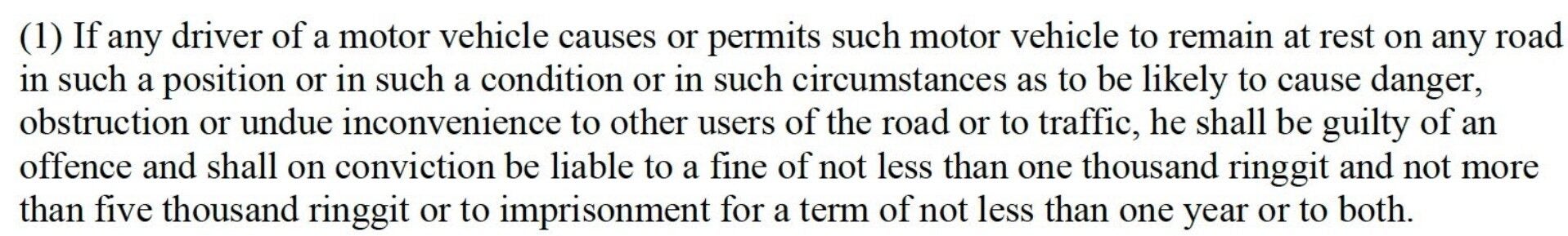

1. Section 48(1) of the Road Transport Act 1987

Speaking to WORLD OF BUZZ, Irzan Iswatt, a partner at Kuala Lumpur-based law firm ADIL Legal, explained that parking in front of someone’s house and blocking the road could get your neighbour in trouble under Section 48(1) of the Road Transport Act 1987.

He said the law makes it an offence to park in a way that causes danger, obstruction, or unnecessary inconvenience to other road users.

2. Malaysians can get fined up to RM5,000

In the context above, parking in front of a neighbour’s house (if it’s on a public road) can be considered an offence if the vehicle is parked in a way that poses a risk, blocks access, or causes trouble for others on the road.

For illustration purposes only

Additionally, Iswatt added that Section 48(2) of the same Act gives the authorities the power to clamp the vehicle’s wheel or have it towed away. The rest of Section 48 lays out the procedures for how the clamping and removal should be done.

Those found guilty can be fined between RM1,000 and RM5,000, jailed for up to a year, or face both penalties.

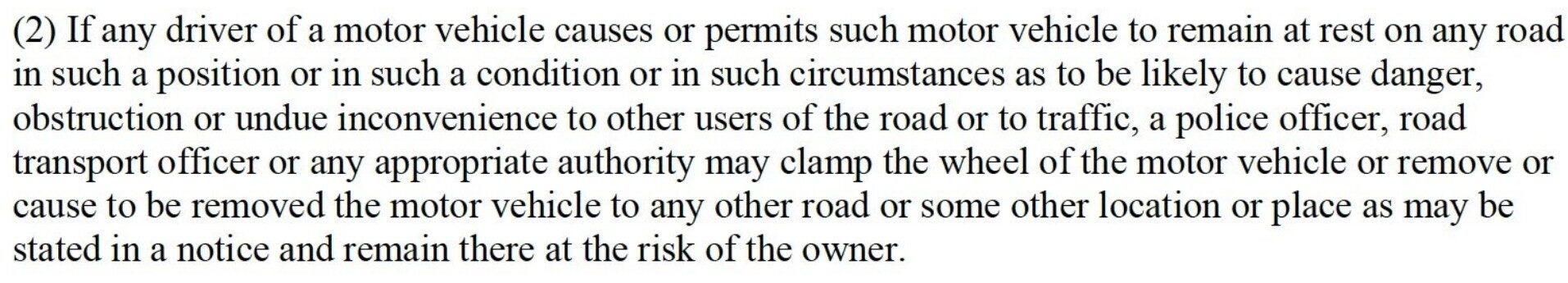

3. The Drainage and Buildings Act 1974 may also apply

Iswatt added that Section 46(1)(g) of the Drainage and Buildings Act 1974 (Act 133) could also come into play, as it covers similar situations involving road obstructions.

For illustration purposes only

The provision states that anyone who causes or allows a vehicle to be parked on a footway is considered to be causing an obstruction. In this case, “footway” refers to footpaths or verandah-ways along the sides of streets, as defined under Section 3 of the Act.

Meanwhile, Section 46 of the Act allows offenders to be arrested without a warrant by the police or authorised local council officers and brought before a Magistrate’s Court.

If found guilty, offenders can be fined up to RM500, and for repeat offences, the fine can go up to RM1,000.

4. Wilful trespassing could land you a fine of up to RM50

Meanwhile, for those who park their vehicles on your property, they could be charged under Section 22 of the Minor Offences Act 1955 for wilful trespass.

The law states that it’s an offence for anyone to intentionally enter someone’s house or land without a valid reason, and if found guilty, they could be fined up to RM50.

For illustration purposes only

5. Entering someone else’s property could get you up to 6 months in jail

Additionally, Iswatt mentioned that entering someone else’s property could also be considered an offence under Section 441 of the Penal Code for criminal trespass.

In this case, a person may be guilty of criminal trespass if they enter another’s property with the intention to intimidate or annoy the person who owns or occupies it.

If found guilty, they could be charged under Section 447 of the Penal Code, which carries a penalty of up to six months in jail, a fine of up to RM3,000, or both.

Civil action under the tort of private nuisance

Besides that, if your neighbour parks their car on your property, you can also consider taking civil action under the tort of private nuisance.

This allows you to sue the person responsible to stop the interference (through an injunction) and claim compensation for any loss or damage caused.

The tort of private nuisance basically deals with interference with one’s enjoyment of their land or property due to the actions of another person. To successfully establish an action under the tort or private nuisance, you must prove these elements:

- There is an interference with the enjoyment of his property

- The interference was unreasonable

- The interference had caused damage

Iswatt elaborated that the interference must also generally be a result of a continuing state of affairs rather than a one-off incident. Moreover, for an interference to be regarded as unreasonable, it must be something that ‘goes beyond the normal bounds of acceptable behaviour’, as established in the case of Au Kean Hoe v Persatuan Penduduk D’villa Equestrian [2015] 4 MLJ 204 FC.

Of course, all of the above actions should be taken as a last resort when attempts at diplomacy fail.

What are your thoughts on this? Let us know down in the comments!