The Malayan Emergency (aka Darurat) was perhaps one of the darkest times in our country’s history. Many atrocities and tragedies happened during this time that will never be forgotten for generations to come. One incident that happened during this period however, has been the subject of a years-long legal battle. On this day 70 years ago (12th December), we remember the two dozen unarmed Malayan men who were killed in what is now known as the Batang Kali massacre.

Here is the story of how the tragedy was widely believed to have happened and the struggles the survivors and the victims’ next-of-kin had to face;

1. The events of a tragic massacre

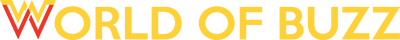

On the 12th of December 1948, 24 unarmed villagers were killed by British troops during the Malayan Emergency period. They were carrying out counter-insurgency operations against Malayan communists. According to BBC News, the British government at the time suspected these villagers were communist insurgents.

On that fateful day, a 14-man Scots Guards patrol went to the Batang Kali rubber plantation in Selangor and rounded up more than 50 villagers. Men were separated from women and children, and the groups were detained in two separate huts overnight, during which time one man was reportedly shot dead. Both groups were then interrogated by the soldiers.

Source: the independent

The following day, the women and children were driven away from their village in a truck. The 23 men were then released from their hut, after which all of them were shot dead by the soldiers for allegedly attempting to escape. The village was then burnt to the ground.

Some accounts stated that the people were killed after attempting to escape into the jungle despite being warned that they would be shot if they tried to run away. However, survivors of the massacre tell another story. According to them, the victims were led out of their homes and shot in the back.

Some of their bodies were allegedly disfigured by the soldiers and “trophy photos” were taken of the victims’ mutilated bodies before the village was set on fire. Official reports from British authorities labelled the villagers as “bandits”.

2. Renewed interest

The incident was largely forgotten by the public and authorities until 1970, when a British newspaper published an account of the massacre, including statements from soldiers who admitted that the villagers were murdered in cold blood.

Source: the guardian

With the help of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), a petition demanding an official apology was sent to Queen Elizabeth II in June 1993, but there was no response. The survivors then launched two separate police reports between 1993 and 1997, but investigations by the Royal Malaysia Police “obtained virtually no assistance and was met with an uncooperative attitude from the UK”. Another petition was sent to the Queen in 2008, but this was also met with no response.

The UK government then rejected a call for an inquiry into the massacre in January 2009, but then announced that they were reconsidering this decision in April of the same year. However, the UK government ultimately decided against an inquiry in the end.

3. The passing of the last living adult witness

A Malaysian woman named Tham Yong was one of the first survivors of the massacre who had filed legal action for Britain’s failure to properly investigate the incident. She had reportedly witnessed her fiancé and other villagers being killed in the massacre.

Tham yong | source: the independent

Tham Yong passed away in 2010 at age 78 and was the last living adult witness of the massacre prior to her death. A family representative was quoted as saying, “With Tham Yong’s passing, we have lost the final adult perspective to what happened in Batang Kali.”

4. Secret documents and future inquiries

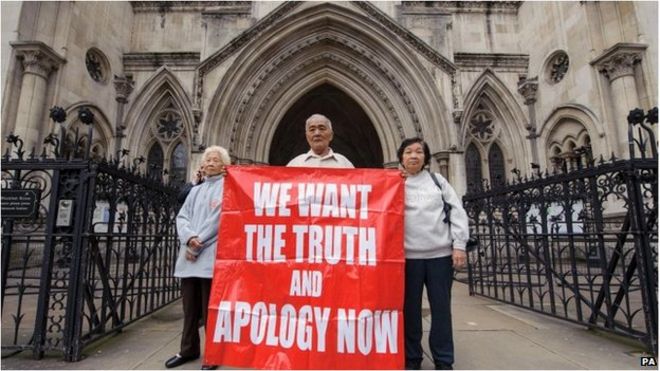

Despite Tham Yong’s passing, the legal battle still went on for years after that. Most recently, an application to the European Court of Human Rights was rejected in October 2018 after ruling that the European Convention on Human Rights could not help the remaining survivors and witnesses to the Batang Kali massacre.

Their reason behind this was because the complaint was not within its jurisdiction as the deaths occurred more than 10 years ago and that the massacre did not have enough new developments to warrant an investigation. This was despite the fact that secret documents regarding the massacre were discovered by Tham’s lawyers a few years prior.

Relatives of the batang kali victims | source: bbc news

One of these documents revealed that the British High Commission in KL told ministers there was no point in British officers from Scotland Yard to interview the massacre’s eyewitnesses in 1970 as “Malaysian villagers were untrustworthy, motivated by compensation and it was ‘doubtful’ they could recall events 22 years earlier.” Another document showed that the colonial Attorney General who acquitted the Scots Guards troops had believed that the killings would deter other communist insurgents.

Despite this decision, the court also stated that they could look into the failure to conduct any inquiry into this incident since it also went against the values of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Batang Kali massacre is definitely one of the many tragic events that took place during the Malayan Emergency. While it may seem like all legal avenues have been used, the UK government can still choose to open a public inquiry into the killings in an effort to bring some closure to the relatives of the victims.

Also read: 30 Years Ago Today: The Tragic Collapse Of A Bridge That Injured Thousands in Penang